Van Gogh and Christmas

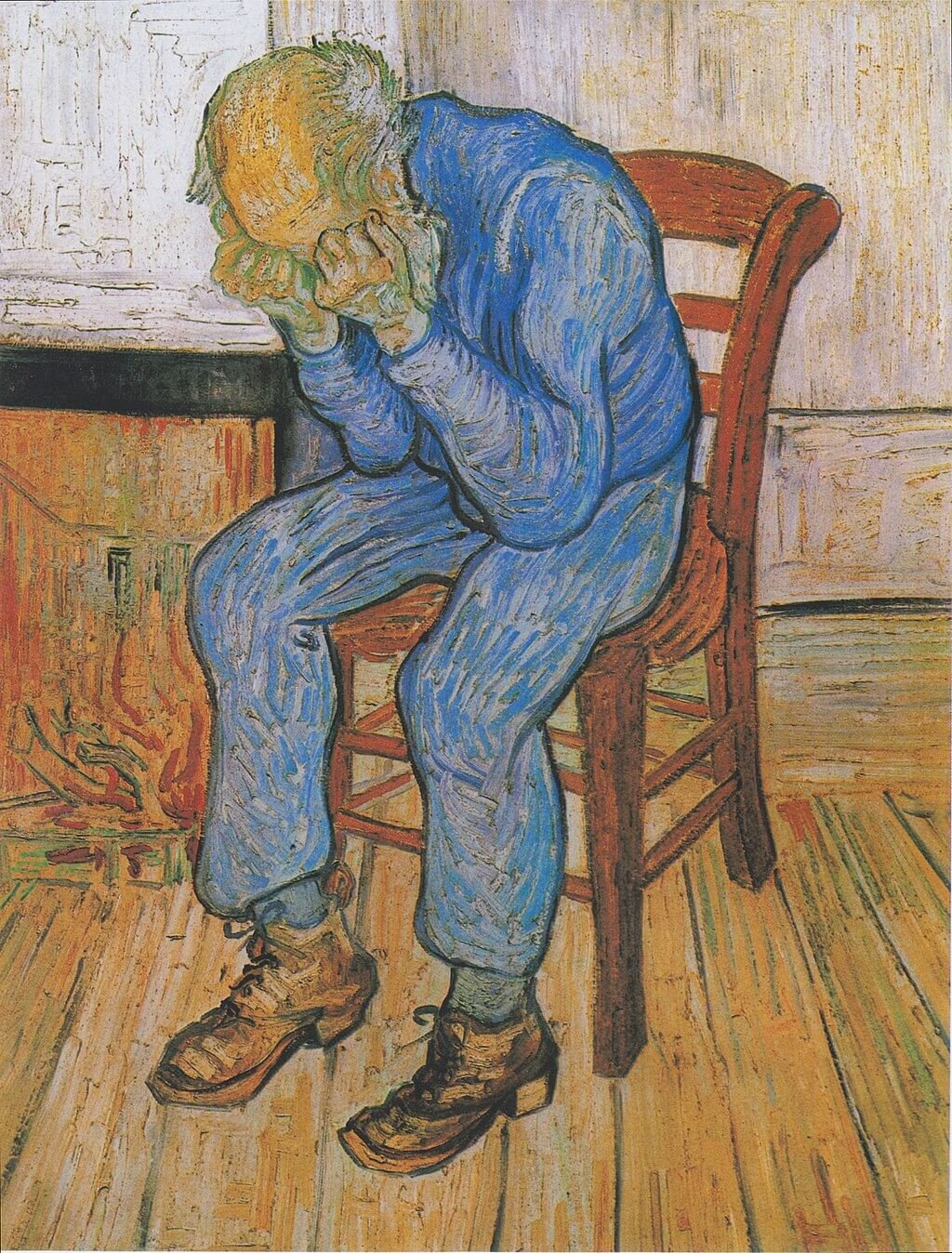

Vincent van Gogh considered “At Eternity’s Gate” (the image above) to be a Christmas painting.

Not exactly a picture of sugarplums, a star and a stable, or a heavenly host! To understand Vincent’s thinking here, we need to turn to his correspondence — and in particular, to two letters he wrote to his younger brother, Theo, right around this time of year, in late November and December of 1882.

“My intention” with this portrait of an old man, Vincent wrote, was “to express the special mood of Christmas and New Year” — for in this image, we can catch sight of the core “sentiment” of the Christmas season.

What sentiment, exactly? Vincent put it this way: “I was trying to say… that one of the strongest pieces of evidence for the existence of ‘something on high’ in which [the painter] Millet believed, namely in the existence of a God and an eternity, is the unutterably moving quality that there can be in the expression of an old man like that, without his being aware of it perhaps, as he sits so quietly in the corner of his hearth. At the same time something precious, something noble, that can’t be meant for the worms…”

“This is far from all theology,” Vincent continued, “simply the fact that the poorest woodcutter, heath farmer or miner can have moments of emotion and mood that give him a sense of an eternal home that he is close to” (Letters to Theo, #288, #294).

In other words, for Van Gogh, not only in times of joy and merriment, but also in times of difficulty and despair, traces of human dignity — “something precious, something noble” — shine through, providing “a sense of an eternal home,” a vivid glimpse of “eternity’s gate.” And that vivid glimpse, whether in joy or in sadness, is for Vincent what Christmas is all about. At the manger’s side, we might say, we arrive at the threshold, the gate, the vantage point — if we have eyes to see.

All of which evokes one other Van Gogh masterpiece (the image below) that, for him, was a kind of Christmas painting: “La Berceuse (‘The Lullaby,’ or ‘Woman Rocking a Cradle’),” a portrait he completed during the Christmas season of 1888.

For Vincent, “the eternal poetry of the Christmas night” comes down to Mary and Joseph huddled around the infant Jesus — a scene epitomized, Vincent wrote, in a simple wooden cradle: “if one feels the need of something grand, something infinite, something that makes one feel aware of God, one need not go far to find it. I think I see something deeper, more infinite, more eternal than the ocean in the expression of the eyes of a little baby when it wakes in the morning, and coos or laughs because it sees the sun shining on its cradle. If there is a ‘ray from on high,’ perhaps one can find it there” (Letters to Theo, #245, #292).

“La Berceuse” is a portrait of a woman holding a rope used to rock a cradle back and forth in the night. Vincent wrote to Theo, “the idea came to me to paint a picture in such a way that sailors, who are at once children and martyrs, seeing it in the cabin of their Icelandic fishing boat, would feel the old sense of being rocked come over them and remember their own lullabys” (Letter to Theo, #743).

Telling, too, is how Vincent envisioned arranging “La Berceuse” in a triptych: three paintings side by side, “La Berceuse” in the middle, flanked on the right and left by portraits of sunflowers (Letter to Theo, #776).

With all of this in mind, we may interpret “La Berceuse” as nothing less than a kind of Madonna, or even a divine portrait: the loving Mother who comforts and cares for us with a lullaby, a Christmas altarpiece for the ocean, and by extension, for all of creation. And accordingly, whenever we look at this painting — as countless thousands now have (it’s at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City) — we take up the position of a child in a cradle, rocking and listening and remembering home, like sailors out on the open, starlit sea.

Merry Christmas,

The SALT Team