The Great Reversal

In 1975, in the midst of his 27-year imprisonment, Nelson Mandela wrote to his wife, Winnie, a prominent leader in her own right who was facing imprisonment: "Incidentally, you may find that the cell is an ideal place to learn to know yourself, to search realistically and regularly the process of your own mind and feelings."

This was no romanticization of captivity, of course, but rather a poignant word of encouragement to his spouse and partner. And at the same time, it was a striking, paradigmatic example of one of the secrets of Mandela's success, a kind of signature move that goes to the heart of his distinctive genius.

Mandela had an extraordinary ability to discern and perform a special kind of reversal. He knew how to take adversity, even one of the most severe forms of adversity imaginable (imprisonment in Robben Island, that remote, inhospitable "Siberia" of the apartheid-era South African prison system), and transform it into a tool of empowerment and resistance.

As the book and film Invictus made famous, Mandela could take a long-divisive symbol — the green and gold Springboks rugby jersey, beloved by the white Afrikaner minority and loathed by the black majority — and turn it into a sign of national unity and pride. When he wore the jersey out onto the field of the 1995 Rugby World Cup final, it caused a sensation. The delighted crowd spontaneously erupted into a roaring chant, "Nelson! Nelson! Nelson!"

A symbol of division, reversed and remade into a symbol of unity. Likewise, Mandela's emergence from prison could easily have been an occasion for a call to vengeance and civil war, but he reversed that expectation entirely, transforming the moment into an occasion for a call to reconciliation and democracy.

Mandela's prison cell in Robben Island, then, is yet another instance of this signature reversal. A room meant to break his spirit, remade into a room that strengthened it. A prisoner's cell of confinement, recast as a monk's cell for self-examination. A cage designed for bondage, now transformed into a pilgrimage site, a shrine to the liberty of the human heart.

There is a deep defiance in this moral jujitsu, a refusal to give in not only to the oppressor, but also to the very idea of oppression itself. Such defiance can flow only from profound conviction, along with deep self-knowledge and self-confidence. Mandela knew who he was. Accordingly, throughout his life, he carried himself with a dignity and grace that few have matched on the world stage.

But if he knew who he was, it's equally true that for him, as for each of us, that self-knowledge was hard-won. Indeed, his letter to Winnie is also a window into his own disciplined commitment to "know thyself," as the ancients put it, to "search realistically and regularly the process of your own mind and feelings."

And so as we say farewell to this giant — husband and father, revolutionary and reconciler, prisoner and president — we truly honor him only if we seek to follow his example, both in terms of his discipline and in terms of his creative ambition. There are divisions right here at home, in Indianapolis, in Indiana, and beyond; plenty of occasions ripe for vengeance; and even more experiences of adversity, discouragement, suffering, and despair. Each of us can identify a range of ways in which we are captives, ways in which we continue to require liberation.

The artful thing, the thing Mandela would encourage us to do, is this: to embrace these adversities in ways that reverse them, turning them into opportunities for progress and flourishing. To strive, in disciplined and creative ways, to know ourselves individually and communally, examining "realistically and regularly" our common life together.

For example: Can we seize upon Indiana's infamous historical connection to the Ku Klux Klan (so powerful here less than 100 years ago), and resolve to become the country's most welcoming, just, reconciling place to live? Can we turn and reverse a caustic history of racism into a legacy — a truly Hoosier legacy — of equality, fellowship, and hope?

Of course we can. But not without each other, not without disciplined commitment, and not without inspiring exemplars such as Nelson Mandela, golden lanterns to help guide us on the way.

The time is right for this kind of renewal. Christmas, after all, is a season of great reversals. The story begins with a young woman in a forgotten town, singing a song of praise about how God has "lifted up the lowly." Mary's song is typically called the "Magnificat." And it is magnificent, isn't it? How the tyrants fall? How prisoners become presidents? How even and especially those things that keep us captive can be recast, and reversed, and transformed — and make us free?

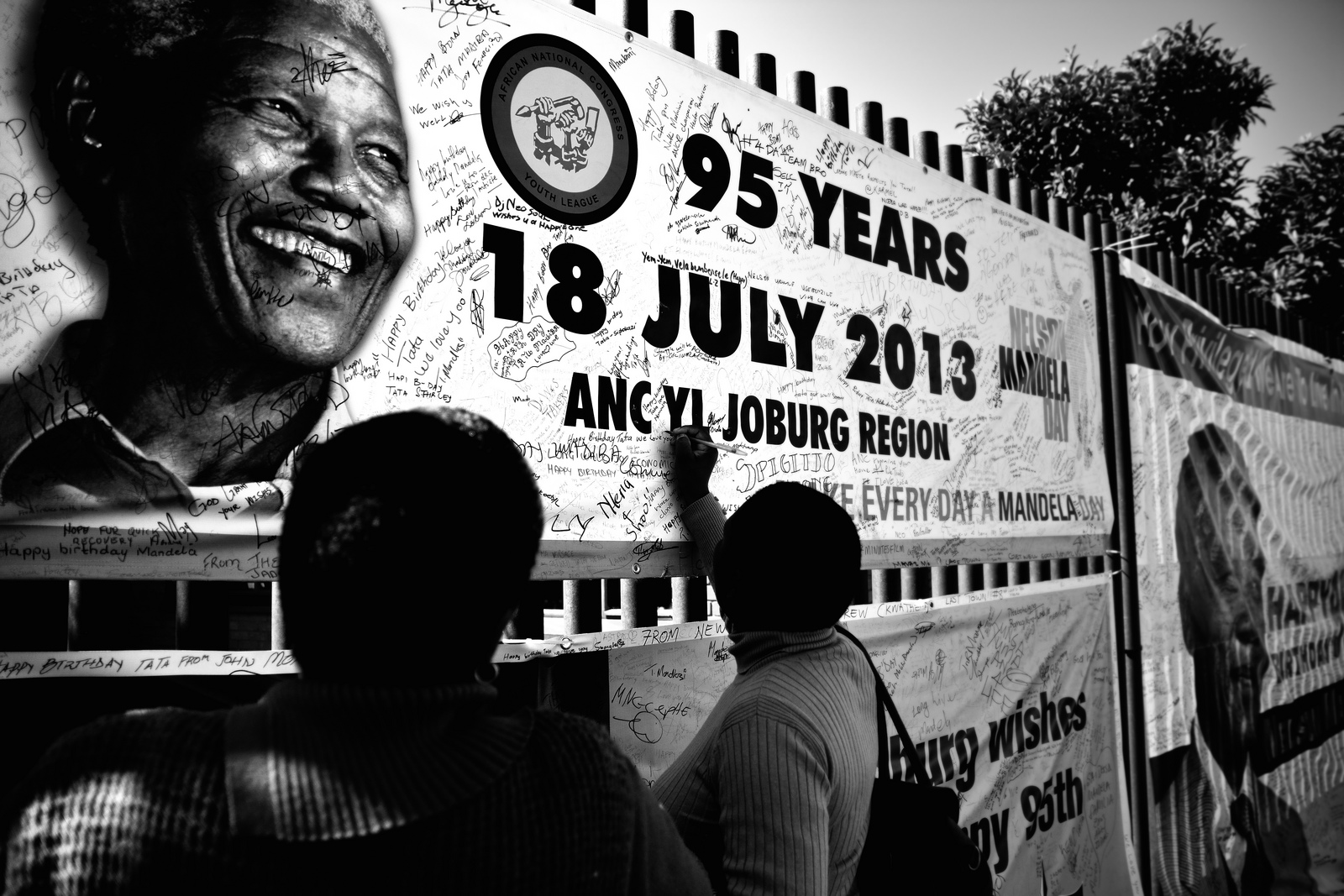

A big SALT thank to Matthew Myer Boulton, professor of theology and president of Christian Theological Seminary, for penning this exquisite essay published today in Nuvo. And, thank you to Andrea Cavallini for capturing this stunning moment and this giant of a man!